Isn’t it about time mainstream media paid attention to all the good work going on at running events these days?

Guest Viewpoint by Keith Peters

Don’t get me wrong—I loved all the attention the Virgin Money London Marathon got for their pilot program of edible/biodegradable capsules made from seaweed. News outlets ranging from the BBC, CNN, NPR, NY Times, and Forbes all ran stories about London Marathon organizers replacing thousands of plastic water bottles with seaweed sachets at one aid station in a pilot program. But I’d suggest that those same news outlets, along with their regional and local counterparts, are missing lots of great stories about environmental, economic and socially responsible initiatives at running races all across the USA and around the world every weekend.

OK, I’ll get off my soapbox now, and will try to do justice to the story of the seaweed sachets and other pilot projects at this year’s Virgin Money London Marathon. But I’ll continue to lament the fact that there are a lot of interesting and innovative initiatives being undertaken in the endurance sports world that are going unreported every day.

To put the seaweed sachet pilot project in context, it’s important to note that London Marathon Events Ltd (LME) have a very clearly stated environmental policy posted on the Virgin Money London Marathon website, and are unequivocal in their commitment to becoming a world leader in delivering sustainable mass participation events, with an ambitious goal of zero waste to landfill by 2020.

Sachets of hydration made of an edible seaweed-based cellulose were tried out at the 2019 Virgin Money London Marathon to reduce waste generation by eliminating the cups used to deliver water and sports drinks to participants during the race.

A bottle belt trial enabled 700 runners to carry their own fluids with them throughout the event.

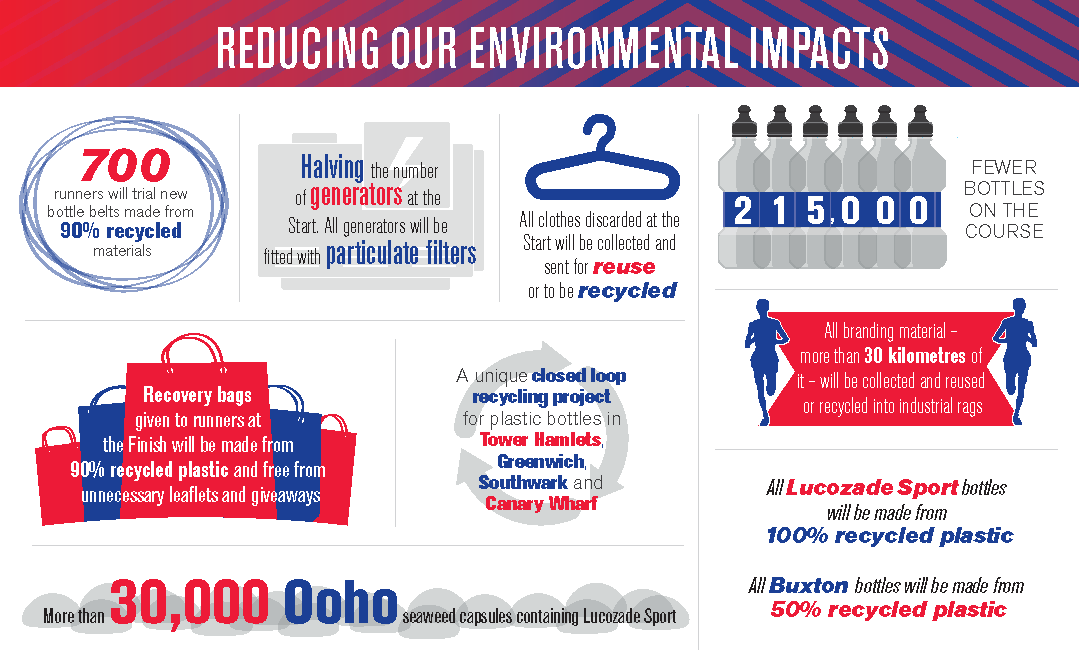

It should also be noted that the seaweed sachet pilot was just one of many successful trials at the marathon this year. Among the others were: an overall reduction of 215,000 plastic water bottles on course; a closed-loop plastic bottle recycling project in four London boroughs; a bottle belt trial that enabled 700 runners to carry their own fluids with them throughout the event; and 500 specially designed Virgin Money London Marathon capes that were given to runners at the start and finish to keep them from having to discard clothing at the start and/or having a bag full of gear to pick up at the finish. Capes that were worn and discarded at the start were collected and washed for reuse, as were capes distributed at the finish and returned to LME through the Postal Service.

(Image via: London Marathon Events, Ltd.)

But the news hook was clearly the largest ever trial of Ooho seaweed edible and biodegradable capsules, dubbed edible water bottles by Wikipedia. Following a successful trial at The Vitality Big Half, LME staff and Lucozade Sport worked with Skipping Rocks Lab on a test of more than 30,000 30 mL Ooho capsules at the Lucozade Sport Station at Mile 23 of the Virgin Money London Marathon. (Once the Ooho capsules were used up, volunteers distributed Lucozade in compostable cups instead.)

While anecdotal feedback was largely positive, LME staff, Lucozade and Skipping Rocks lab will spend the next couple of months reviewing runner surveys before sharing their learnings and recommendations re the seaweed sachet pilot and other trials with running industry leaders. There were, however, a few early observations about the sachets that are worthy of note:

Faster runners appeared to have more trouble grabbing the sachets from volunteers than slower runners did.

While 30 mL capsules are the ideal size for a sports drink like Lucozade, they may be too small for efficiently dispensing water.

Use of the seaweed sachets made for cleaner roads near the 23-mile aid station, and much quicker clean up.

Future trials should include making capsules available to runners at the expo so they have a chance to try before race day.

In researching this column, I was pleased to have the full cooperation of Tom McGlynn, LME’s Operational Planning Technician and Sustainability Lead. Over the course of our conversations he shared a couple of thoughts that, I think, are applicable to the sustainability efforts of any road race, anywhere:

It’s going to take a few years and endless tweaking; there are no simple solutions.

You need to balance operational needs and environmental goals with runner welfare and event experience.

Finally, when I asked Hugh Brasher, Event Director for London Marathon Events, what inspired LME to take such a different and counter-intuitive approach to testing lots of things at one event, he replied: We only produce one marathon a year; we’ve produced 39 in total. We’ve got to try as many things as we possibly can every time out.

Brasher also mentioned a key thought he picked up from Danone CEO Emmanuel Faber at a recent Sustainable Brands conference: All organizations, regardless of sector, need to be bold in their approach to sustainability. Otherwise they face the prospect of being useless.

Keith Peters first organized running events for students at the University of Tennessee, Martin in 1978, and was involved in producing the Cascade Run Off from 1981-93. For the past 11 years, he has worked with scores of road races seeking verification and recognition of their efforts to become more sustainable. He is currently a board member of the Council for Responsible Sport.

This article was originally published as a ‘Going Green’ column in the Road Race Management newsletter and has been republished here with the permission of the author.